05 Jun The benefit of breaking the rules

Did you ever do something as a child knowing full well that you were going to get in trouble, but you couldn’t let that stop you?

I’m not talking about sneaking treats from the cookie jar when no one was looking or playing outside past when the streetlights came on. I’m more alluding to a compulsion you had to do something which, for one reason or another, had been deemed “against the rules” by Mom or Dad.

This might be showing my age a little bit, but when I was in 5th grade my father stated very plainly that I was no longer allowed to move the VCR out of the family room. He would regularly come home from work and be unable to watch TV because the back of the box was a mix of disconnected coaxial cables. A minor inconvenience, sure, but in his mind the constant shuffling of electronics up and down the stairs was bound to end in a broken piece of equipment. So, on a dark day in the Staples household, he banned my newfound hobby.

What my father didn’t know was that what started as a way to rob the local video store of repeat rentals soon became my first foray into the world of video editing.

That previous summer, I was walking home from my grandparents’ house a few streets over and passed a little old lady having a little old yard sale. To this point in my young life, the only televisions in the house were in the living room and my parents’ bedroom. A blooming cinephile and Simpsons obsessive, I had asked for a TV/VCR combo repeatedly only to be told that I could get one when I paid for it. No amount of lawns mowed or babies sat could provide the capital needed for a purchase of this magnitude. That was until today.

Staring back at me from this neighbor’s patch of grass was a 13” black-and-white Zenith and a Panasonic top-loading video cassette recorder. The poor woman had no idea what she had on her hands. For the grand theft price of $10, this haul of late 1970s technology was mine for the taking. I ran the 500 yards home, grabbed a crisp Hamilton from the secret envelope of cash in my desk drawer earned from shoveling snow, and sprinted back to claim my wares.

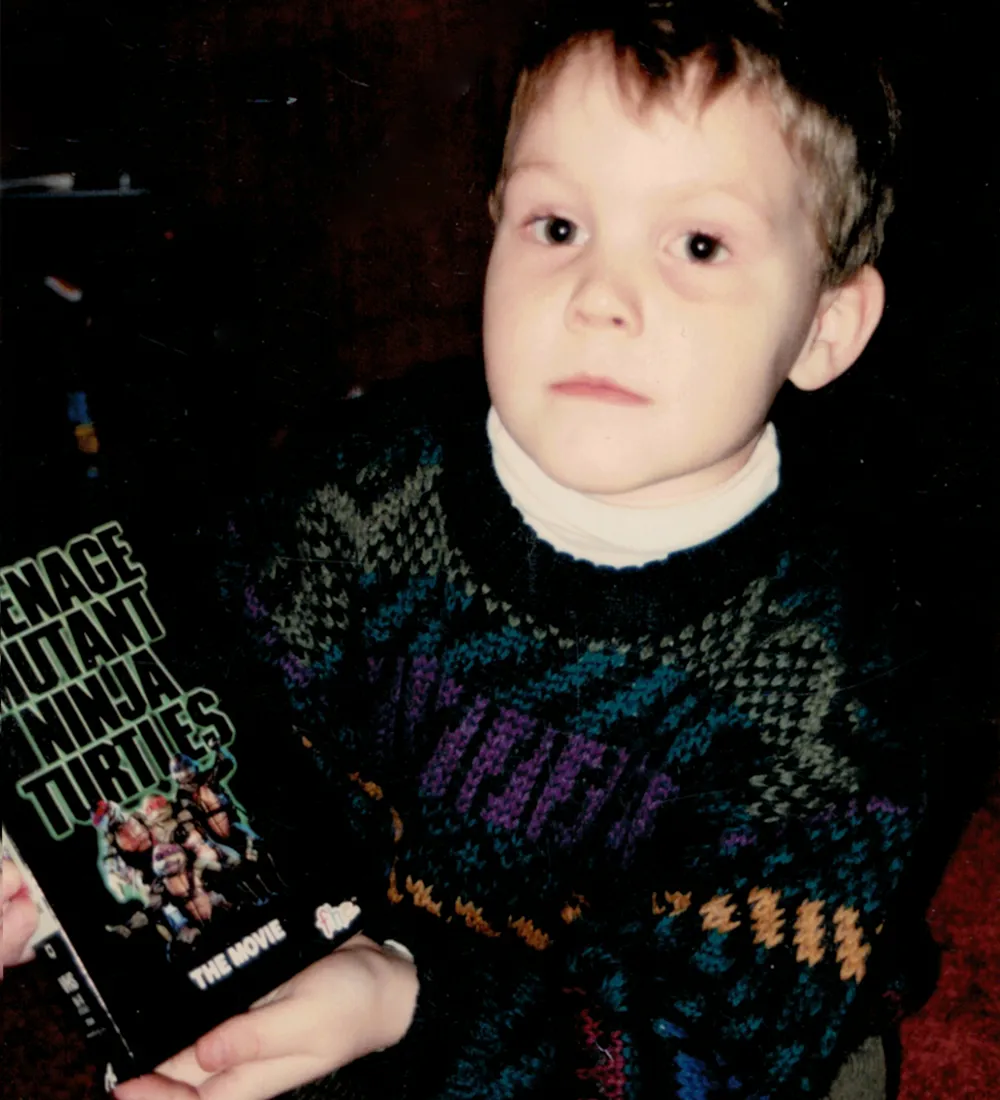

I was overjoyed. It didn’t even matter to me that, for years drained of color, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles all had bandanas with slightly different shades of gray.

SOURCE: File Photo, Christmas 1990

Growing up, our movie collection was mostly comprised of things that my mother had taped off cable. In my recollection, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off has a JC Penney commercial right after Ed Rooney gets punched in the face. I had been to other kids’ houses and seen shelves of legitimately purchased videotapes, so I wondered if it was possible to somehow make a copy of Pee Wee’s Big Adventure that wasn’t the NBC Sunday Night Movie sponsored by Tide.

A short trip to Radio Shack later, after describing my predicament to the more-than-patient clerk behind the counter, I had a 3-pack of blank VHS tapes and all of the cables needed to complete my experiment. What I needed now was the downstairs VCR.

In those first few weeks, my success knew no bounds as I amassed a growing stockpile of duplicates for a fraction of the price it would’ve cost to buy them. Little did I know, my father was days away from bringing down the hammer. Though, before he did, I discovered the joy of making “video mixtapes.” I’d assemble a collection of funny scenes from a variety of movies onto one tape and pass that around to either my cousins or other kids in class. Though, after almost recording over a home video and nearly erasing my brother’s entire 1992, I realized that these tricks could be applied to my own movies.

Like most kids who were lucky enough to get their hands on a camcorder but didn’t quite have a grasp on the art of production, I would make short films shot entirely in sequence. Constantly changing camera angles, rewinding sometimes not far enough after blown takes, and inconsistent light given the hours it would take to film a two-minute scene resulted in, still, a masterpiece in my estimation. But now, with my new setup, I could shoot as much as I wanted and splice it all together in my room later that night. Throw in the idea to run RCA cables from my stereo into the mix and I could now add a needle-drop soundtrack as well. I felt like Scorsese with a lunchbox.

It was just as soon as I came to this realization that the ban was introduced. No amount of pleading with Dad could get him to change his mind. His mark of quality as it pertained to my bad Ghostbusters rip-offs was earned after clearing much lower benchmarks. The arguments of improved production value carried no water with him. So, when pitch after pitch were rejected, I decided that instead of continuing to ask for permission I would ask for forgiveness were I to ever be caught.

For quickness and efficiency, I drew a map in blue crayon of cable and gear assembly, which was a timesaver when I might only have an hour or two to edit when I got home from school. My creativity was put into practice whenever I found myself alone in the house for a healthy stretch of time. Unfortunately for you, these tapes were all lost as I moved around the country in my early 20s. But believe me when I tell you that I made everything from bad courthouse dramas and superhero films to bad late night talk shows and SNL clones. My Dad never caught me. Hopefully he’s not reading this right now or I’m liable to be grounded for the entire summer of 1997.

I tell you all of that to tell you this: every single one of us at Votary has a similar story. Maybe not one laced with so much nerdy defiance, but rather one where the narrator identified very early on in life that they needed to make films. It’s that simple. No person or obstacle could stand between them and their love of movie making. Had I not broken the rules, I’d have missed out on an opportunity to refine a skill that’s served me well for the rest of my life. That’s who you’re working with when you work with us.

And while none of us are still watching the clock, trying to squeeze in one last cut before 5pm so we can return the VCR to the family room – we’re definitely still looking for every opportunity to break rules. Professionally, of course. There’s nothing exciting or appealing about the boiler plate version of your story. We want to be sure that every single film we craft together engages, educates, and entertains not just you, but your audience.

And if you have any desire to get together in the backyard and make a low-rent version of The Sandlot, be sure to give me a call.

If you’re looking to get started on a project, Votary has a passion for telling compelling stories through the art of filmmaking. We specialize in producing brand stories, creative commercials, and documentary series. If that sounds to you like we might be a fit, then let’s talk. Start a Conversation.